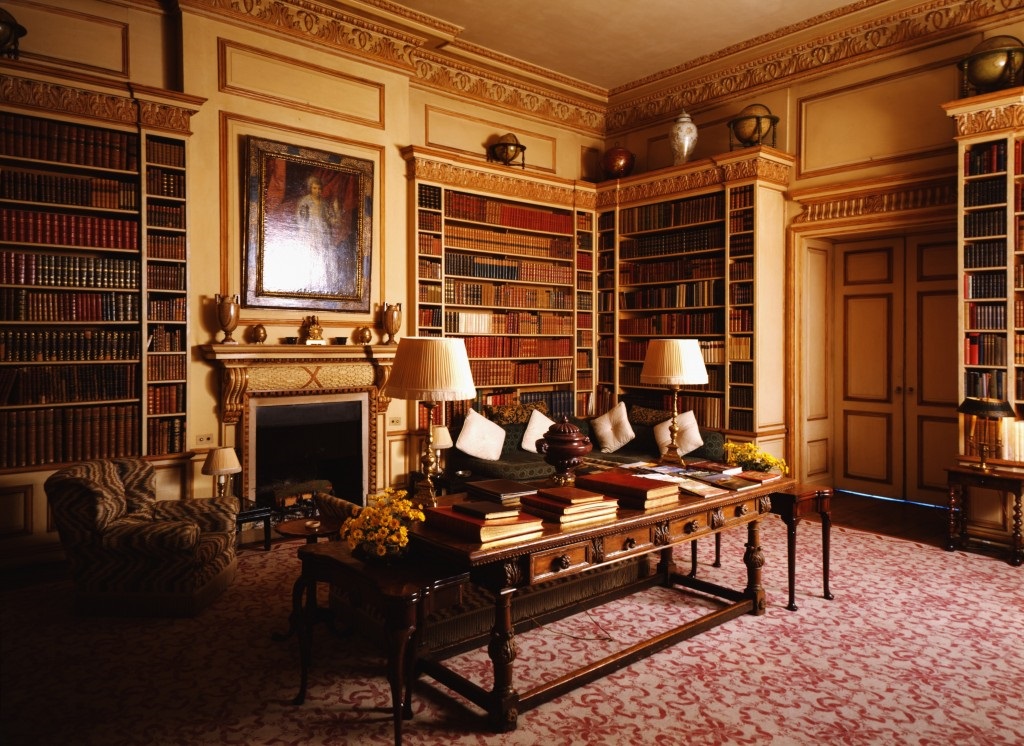

The much acclaimed past television series, Downton Abbey has brought more than just the English country home to our attention. It has accurately depicted an aristocratic lifestyle that was clinging for survival in the early 1900’s and sometimes found financial reprieve from wealthy Americans. The stories behind these ‘marriage mergers’ and influx of wealthy Americans and heiresses to Britain country homes were fascinating and up until now, untold. Clive Aslet, British architectural and lifestyle historian, has written An Exuberant Catalogue of Dreams which features such Americans as the Astors, Vanderbilts, Carnegies, Selfridges, Hearsts and others who helped save many a English country home so that they could live to see another day.

‘An Exuberant Catalogue of Dreams’

by Clive Aslet

‘Clive Aslet is an award-winning writer and journalist, acknowledged as a leading authority on Britain and its way of life. In 1977 he joined the magazine Country Life, was for 13 years its Editor and is now Editor at Large. He writes extensively for papers such as the Daily Telegraph, the Daily Mail and the Spectator, and often broadcasts on television and radio.’

We are thrilled that he was able to sit down with the Artisans List for an interview to give us even further insight into this period of time and his book.

Artisans List: Mr. Aslet,what prompted you to write this book?

Clive Aslet: When my publisher at Aurum suggested that Americans who have owned, altered, restored and rescued British country houses might make a subject for a book, my first thought was that it must have been done. I then found that, to my surprise, nobody had written about it. It was calling out for treatment.

So many Americans have owned or married into country houses. There were, of course, the heiresses. Agriculture went into a long recession in the 1870s and this meant that many aristocrats, who owned landed estates, were hard up – just at the time when the rise of the plutocracy meant that fashionable life was becoming more expensive. Some of them looked across the Atlantic to the great industrial fortunes being made there and thought that they could get (in the slang of the day) ‘plenty of tin’ through marriage. One of the first to do so was Sir Thomas George Fermor-Hesketh who married Flora Sharon, daughter of an extremely rich, if notorious banker, Senator Sharon, in San Francisco. They sailed back to Easton Neston, in Northamptonshire, on his yacht, where Flora’s money was responsible for the redecoration of the family seat (or seats, because they had more than one). By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, nearly a fifth of the peerage had American connections.

The American girl was regarded as a type – better educated and more ‘sparky’ than her British equivalent. Not all marriages between American money and British titles were happy, but the Marquess of Curzon worshiped Mary Leiter. She accompanied him to India when he was Vice-Roy and occupied the highest position that it was possible for a commoner to hold. May Goelet, who had been Consuelo Vanderbilt’s bridesmaid, had a wonderful time in the capitals of Europe, being pursued by dashing, if sometimes impecunious admirers. She surprised friends by accepting the proposal from the 8th Duke of Roxburghe, and becoming an admirable Duchess in Berwickshire.

There were also men who came to Britain and built houses. Andrew Carnegie, supposed to be the richest man in the world, had left Scotland when he was a small boy. He built Skibo Castle in Sutherland so that his daughter Margaret would have a taste of Highland life. William Waldorf Astor left the US because he hated the intrusive press. He bought dual Cliveden House, on a bluff overlooking the Thames, and Hever Castle, where Anne Boleyn had spent part of her childhood, in Kent.

After the First World War, the balance changed. Britain was exhausted by the war in Europe, which had taken a particularly harsh toll of the ruling class. Led by the Prince of Wales, future Edward VIII, country house owners looked with envy at the efficiency and modernity of the American home. Americans became leaders of society in Britain.

All this struck me as a rich theme. American money has been responsible for propping up some of our loveliest country houses, and who knows what would have happened if it hadn’t been there? I thought it was about time somebody said, Thank you.

AL: An Exuberant Catalogue of Dreams – that is an unusual title. How did you come up with that?

CA: It was a phrase that the architect Philip Tilden used of the castle which he was commissioned to design for the owner of the Selfridge department store, Gordon Selfridge. The castle was conceived on a megalomaniac scale and never built, but I thought the phrase ‘exuberant catalogue of dreams’ expressed something about the period. It was an age when people with enough money could let their domestic imaginations off the leash.

AL: With Nancy Lancaster in the lead, how great an impact do you feel the American-born British aristocracy had in setting the trends in English decorating today? Who else would you put as a leader in the English Country Decorating movement – American or English?

CA: It’s an irony that it took an American, Nancy Lancaster, to establish the country-house look, which even now is taken to be the quintessence of British taste. She came from Virginia, where she had already restored a family house with the help of William Delano, of Delano and Aldrich. She was particularly anxious that the house should be revived without driving away the ghosts. The houses that she and her husband Ronald Tree inhabited in England – first Kelmarsh Hall, then Ditchley Park – were similarly shabby, but with good bones. After the Second World War, her consummate eye was put at the service of other country house owners when she ran Colefax and Fowler with John Fowler.

For decades, the Nancy Lancaster style reigned supreme. Then came agony of minimalism in the 1990s and 2000s. But comfort, thank heaven, has come back, along with wit, exuberance and colour. Robert Kime has many of the Nancy Lancaster qualities – the ability to make a room seem quietly and attractively ‘right,’ as though there could be no other way.

CA: It’s an irony that it took an American, Nancy Lancaster, to establish the country-house look, which even now is taken to be the quintessence of British taste. She came from Virginia, where she had already restored a family house with the help of William Delano, of Delano and Aldrich. She was particularly anxious that the house should be revived without driving away the ghosts. The houses that she and her husband Ronald Tree inhabited in England – first Kelmarsh Hall, then Ditchley Park – were similarly shabby, but with good bones. After the Second World War, her consummate eye was put at the service of other country house owners when she ran Colefax and Fowler with John Fowler.

AL: What would you say is the legacy the American infusion of money and influence from that period had on the English country homes?

CA: There are a number of country houses which mightn’t be standing up at all if it weren’t for the infusions of American money that they received in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Others have survived as private homes, when in other circumstances they would have had to become institutions. The First World War was a greater watershed in the UK than it was in the US. Afterwards Britain was on the decline, America in the ascendancy. Most of our big country houses were very creaky and impractical. Americans insisted on proper bathrooms, central heating and electric light. Wilfred Buckley at Moundsmere is an interesting example: the pioneered clean milk after his wife, Bertha, an American, nearly died of an infection of the tubercular glands. American domestic life was more efficient.

We also owe a tremendous debt to American generosity towards British institutions. For example, J.Paul Getty II, Sir Paul Getty — transformed the fortunes of the national gallery and the British film institute through his philanthropy. The former, ironically perhaps, was given the fighting fund it needed to oppose the might of the Getty museum in California – the creation of Sir Paul’s father. But his largess also helped many smaller and more quixotic causes, from Lord’s Cricket Ground to cathedrals and churches, from the steamship SS Great Britain to a home for retired actors. He didn’t go so far as to play cricket himself but created one of the most beautiful cricket grounds in England at his country